Link: https://www.mdpi.com/2072-6694/12/12/3503

Full text: https://www.mdpi.com/2072-6694/12/12/3503/htm

Simple summary

Asymptomatic meningiomas are present in 1 to 2 % of the cranial MRI. Most of them have no growth or minimal growth and are observed during monitoring imagery. However, patients are faced with a diagnosis of brain tumor . Until now, there is no distress screening established for these patients . In this study, we evaluated the psychological charge of patients with small asymptomatic meningiomas and compared it to that of patients who underwent a complete resection of meningioma and having obtained excellent postoperative results. We have found a high prevalence of the symptoms of anxiety and depression in the two study groups. This shows that even patients with benign asymptomatic intracranial tumors can be in great distress and need psycho-oncological support.

The diagnosis of intracranial meningiomas as fortuitous discoveries increases thanks to the increasing availability of diagnostics by MRI. However, the psychological distress of patients with accidental meningiomas in the context of a waiting and monitoring strategy is unknown. To fill this gap, we therefore sought to compare the psychosocial situation of patients with meningioma in the context of a waiting and monitoring strategy to that of patients after full resection. The inclusion criteria for the prospective monocentric study were either accidental meningioma in the context of a waiting and monitoring strategy , or the absence of neurological deficit after complete resection.

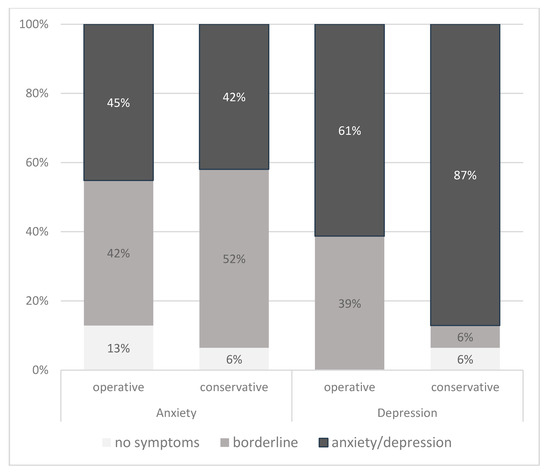

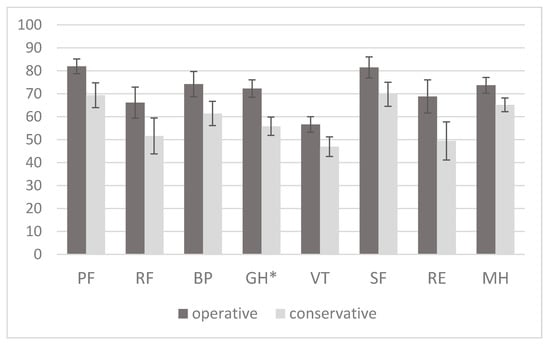

Quality of life and socio -demographic clinical data relating to health have been assessed. Psychosocial factors were measured by the distress thermometer (DT, Distress Thermometr ), the hospital anxiety and depression scale (HADS, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale ), the brief inventory of fatigue (BFI, Brief Fatigue Inventory ) and the abbreviated form (SF-36, Short Form ). A total of 62 patients was included (n = 51 women, average age 61 (SD 13) years). According to HADS, the prevalence of anxiety was 45% in the postoperative group and 42% in the waiting and monitoring group (p = 0.60), and depression was 61% and 87%, respectively (p = 0.005) . In total, 43 % of patients under surveillance and 37 % of patients in the postoperative group obtained the score ≥6 on the DT scale. The SF-36 scores were similar in all categories, with the exception of the general state of health (p = 0.005) and the overall score of the physical component (43.7 (13.6) against 50.5 (9.5), (p = 0.03), both inferior in the waiting and monitoring group. Multivariate analysis revealed that the waiting and monitoring strategy was associated with a risk of 4.26 times. to HADS (p = 0.03) .

Keywords: anxiety; depression ; meningioma; psychological distress; quality of life; surgery ; waiting and surveillance.

Whole study

1. Introduction

Meningiomas are among the primary tumors of the most frequently diagnosed central nervous system, representing about a third of all cases . These are generally slow growth lesions, most often diagnosed in elderly patients and women. Asymptomatic meningiomas can be found in 1 to 2 % of cranial MRI. Due to the growing availability of diagnostic imaging, the number of patients with fortuitous meningiomas has increased. The majority of these neoplasms only have a minimum growth; Consequently, a waiting and monitoring strategy or a conservative strategy can be implemented until the lesion is significantly more important or becomes symptomatic. Consultation of patients with accidental meningiomal for surgery or waiting and monitoring strategy is a challenge and requires sensitive skills.

At the same time, the diagnosis of a brain tumor is generally associated with an important physical and psychosocial burden, regardless of the tumor entity . With the cognitive state and performance, psychological well-being is one of the main indicators of quality of health related to health (QVLS) . Patients with meningioma declare a quality of life linked to health less good than that of healthy witnesses after the operation, and even if it is better than that of patients with glioma, this difference between groups of patients with brain tumors is not clinically relevant. However, to our knowledge, most studies have evaluated patients with a brain tumor who have undergone surgery: QVLS and psychological distress decrease after the operation, but the data concerning normal is contradictory.

On the other hand, there is little data on the psychological charge and the QVLS of patients with a brain tumor as part of a waiting and monitoring strategy without diagnosis confirmed by histopathology. A patient with a small asymptomatic meningioma faces a diagnosis of a brain tumor and, in most cases, a recommendation for a monitoring MRI without any other support measure such as a psycho-oncological support. These patients are seen less frequently, generally once a year or two, as recommended by guidelines. There is no questionnaire on the QVLS specific to meningioma and, unlike patients with glioma, there is no screening of the established distress. Identification of patients in distress in this group could help develop better monitoring, treatment and support strategies for patients.

The objective of the study was to study the psychological load of patients with meningiomas with a recommendation to wait and monitor, compared to patients with a good result after complete resection.

2. Results

2.1. Patients

Sixty-two patients in total (51 (82 %) of female sex, average age 61 years (standard deviation (and) 13)) participated in the study. The detailed characteristics of the patients are presented in Table 1 (click on the link to see the table ). The groups of pending and postoperative patients were relatively comparable, with around 36 % of patients with convexity meningiomas. The women/men ratio and the proportion of patients living with a partner were similar. Patients in the waiting and monitoring group were slightly older (66 (and 12) against 57 (and 13) years, p = 0.008). More than 90 % of the evaluated patients had a performance status of the East cooperative oncology group (ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group ) of 0 or 1 in the two groups. The average score of neurological evaluation in neuro-oncology (nano, neurologic assessment in neuro-oncology ) was 0.4 (and 0.9, interval 0-4) and was similar in the two study groups. A total of 14 (23 %) patients received 1 or more point. Two (6 %) patients were under surveillance and one (3 %) patient in the postoperative group was diagnosed as having a psychiatric disorder. There was a significant difference in the size of meningioma before the operation compared to the group's patients under surveillance (30 mm (and 18) and 18 mm (and 10), respectively, p = 0.016). The average time elapsed since the diagnosis of meningioma in the pending group and the time elapsed since the operation were comparable (39 (and 47) and 32 (and 44) months, respectively). Tumor growth has been observed in six (19 %) patients in the pending group. A relapse of the tumor was diagnosed in two (6%) patients after the meningioma operation. Four (15 %) type II meningiomas of WHO were noted; However, no patient has received radiotherapy or alternative treatment methods in either group. The use of steroid drugs was not discussed during maintenance.

2.2. The psychological charge as measured by the HADS and the DT

The average score on the hospital anxiety and depression scale (HADS-A) was 10.0 (and 2.0, 4-14 interval) in the waiting and surveillance group and 10.0 (and 1.8, interval 6-14, p = 0.92 in the postoperative group. The HADS depression score (HADS-D) was 11.3 (and 1.9, interval 4-14) and 10.9, respectively (and 1.5, interval 8-13), p = 0.23. No statistically significant difference between groups was noted for the HADS-A scale (p = 0.60); however, a significantly higher number of patients in the waiting group and surveillance presented pathological values on the HADS-D score (p = 0.005).

The distress thermometer (DT) has shown significant psychological distress in a large proportion of the two study groups. The average DT score in waiting and intervention groups was comparable (4.9 (and 2.0) against 4.1 (and 2.9), p = 0.31). However, 43 % of pending patients and 37 % of patients in the postoperative group presented significant distress, that is to say a DT value ≥ 6. DT analysis has shown that a significantly higher proportion of patients in the waiting and surveillance group had problems of appearance (19 % against 0 %, p = 0.01), oral sores (29 % against 6.5 %, p = 0.02) pain (67.7 % against 41.9 %, p = 0.04) (figure S1). Fatigue was the most common problem identified in the list of problems in the two study groups (55 % in the postoperative group and 48 % in the waiting and surveillance group), followed by concern (45 % and 52 %) and sleep disorders (45 % and 42 %, respectively).

2.3. QVLS as measured by the SF-36

Analysis of the results of the abridged survey on health (SF-36) revealed that there were no statistically significant differences in the perception of health between study groups in all categories, with the exception of the general state of health, which was significantly lower in the waiting and surveillance group (p = 0.005) (Figure 2). The overall score of the physical health component was significantly lower in the waiting and surveillance group (43.7 (13.6) against 50.5 (9.5), p = 0.03); The overall mental health component score was similar in the two groups (39.9 (15.7) against 46.2 (13.3), p = 0.10).

2.4. The fatigue measured by the BFI

The total average score of the brief fatigue inventory (BFI) was similar in waiting and monitoring and postoperative groups (3.3 (1.5) against 3.4 (1.8), p = 0.95). The average values as well as the proportion of patients with clinically significant fatigue (≥7) were similar among the sub-bras, except for the joy of living, where the waiting and surveillance group obtained significantly worse values compared to the postoperative group (Table 2, click on the link to see the table ). The "largest fatigue" was high: 45.2 % in the waiting and surveillance group and 58.1 % in the postoperative group. No correlation was found between the average and the "most important fatigue" and the DT and HADS scores.

2.5. Factors associated with a higher psychological charge

We evaluated the correlation between the results of different measures of psychological distress: the HADS-A and HADS-D scores, the DT score, the emotional role (RE) and the aggregated mental component of the SF-36. Among all the pairs, significant correlations between the DT score and the mental component (RHO of Spearman -0.68, P <0.001) and between the DT and the RE (RHO of Spearman -0.57, p <0.001) were found. To identify the factors associated with significant distress, uni-variated logistic regression has been carried out. As there were few patients without symptoms according to HADS scores, the classification was simplified in two groups: pathological and limit / no symptoms. DT ≥ 6 has also been used to indicate significant distress. The rank of the WHO was not included, because there were too few cases with upper grades. There were no statistically significant associations for DT and HADS-A pathological scores. The waiting and monitoring strategy was associated with a risk 4.26 times higher of pathological score on the HADS-D score (p = 0.03), and the higher nano score (worse) has been associated with a lower risk of depression symptoms (p = 0.04) (Table 3, click on the link to see the table ). The average nano score was 0.2 (and 0.5) in patients with depression symptoms and 1.1 (and 1.4) in other patients. The two factors (nano scores and treatment group) remained significantly associated with depression in the HADS-D in a multivariate model (Table 4, click on the link to see the table ).

As the majority of patients (50 out of 62) were included in 2019, COVVI-19 pandemic did not influence the mental health of most patients . A direct comparison between patients recruited in 2020 and before has not shown significant differences.

3. Discussion

Data on the psychological distress of patients with meningioma are considerably low compared to more aggressive central system tumors, such as gliomas. In addition, we know less about patients treated in a conservative way, because existing studies are mainly focused on pre and postoperative patients. Although this study included only apparently asymptomatic patients with excellent results after a meningioma operation or as part of a waiting and monitoring strategy, we have observed high proportions of significant psychological distress. More than 80 % of patients from the two groups have obtained limit values or pathological anxiety values. Depression values were high in more than 90 % of patients in the two groups. The waiting and monitoring strategy has been associated with a higher risk of depression symptoms, and more than a third of patients from the two groups experienced significant distress according to DT data.

3.1. Depression and anxiety in patients with meningioma

The few existing studies on depression and anxiety in patients with meningioma show higher levels of distress than in the general population-the proportion of patients with HADS-A abnormal scores reached 70 %, and for HADS-D, 30 % in operated patients. In most cases, the symptoms decreased after the operation. A study examining patients suffering from meningiomas and schwannomas of the ponto-cerebellar angle in the context of a monitoring and waiting strategy reported levels of anxiety and clinically relevant depression in a third of the patients. The proportion of anxiety and depression in our cohort was higher compared to other studies. This could reflect certain regional differences. However, a larger multicenter study is necessary to deepen these observations. The average values of the HADS score in our study were approximately twice as high as the value of the normal German population. These results are particularly alarming because a statistically significant difference in the overall survival of patients with meningioma, laminated according to their preoperative HADS-D score, has been reported.

3.2. Quality of life of patients

In our study, the values of the physical health component of the SF-36 were comparable to the values reported in patients with meningioma before and after surgical treatment. After an operation for meningioma, patients generally declare a lower QVLS than that of healthy witnesses, although certain data on patients who have undergone an asymptomatic meningioma operation have shown no significant difference compared to the general population .

On the other hand, data on surveillance patients are lacking. In a study on healthy witnesses, waiting and under-monitoring patients and postoperative patients, a lower QVL level (using SF-36) but intact neurocognitive capacities have been reported in waiting and under surveillance patients. In accordance with our data, patients pending and under surveillance reported a less good QVLS than the group having undergone surgery. A direct comparison between operated and unpaid patients with meningioma is difficult, as the two treatment strategies cannot be offered equally to each patient. However, the results indicate that "wealthy" patients whose results are asymptomatic could suffer from a significant psychological burden .

Even if only a sub-cheer of the General Health and Physical Health component has shown statistically significant differences between study groups, the average scores of all the sub-scals were lower in the surveillance and waiting group. This observation contradicts the ECOG and Nano scales which were similar between the groups, indicating a difference between the QVLS and the physical and neurological functioning of the patient, as measured by the examiner. Psychological distress is an important determinant of QVLS. There was a significant correlation between the SF-36 role-emotional (RE), the scores of the mental health component and the DT but not with the HADS scores of our study. Like each of these scores is a validated instrument, the meaning of these differences is difficult to extrapolate and, in our opinion, underlines many facets of the psychological state of patients with meningioma.

3.3. Fatigue

Up to 50 % of patients with meningioma under surveillance or before the operation suffer from significant fatigue, making it one of the most common symptoms in this group of patients. About 50 % of patients said they had received a meningioma diagnosis six months after the appearance of symptoms, the most frequent being headache, fatigue and cognitive deficit .

Patients with meningioma reported significantly higher pre -post -post -post -post -post -postal levels than normative values. This complies with our conclusions because around 50 % of patients in the two study groups reported significant fatigue. The most frequent problems identified by patients in our cohort were pain, fatigue, worries and sleep disorders. In oncological patients, the presence of fatigue can be disproportionate to the activity carried out and can considerably reduce the quality of life. There is no clear explanation for the prevalence of fatigue in the group of pending patients.

Apparently asymptomatic people can undergo diagnostic imaging for various reasons, for example by participating in research, on the recommendation of a doctor, in the context of professional screening or a company. It may be part of people with non -specific symptoms, such as fatigue, anxiety and depression, which receive cranial imaging. For example, emotional stability is associated with less serious depression and anxiety in patients with a brain tumor [27]. On the other hand, the high prevalence of fatigue in postoperative patients, the outcome of which is also excellent, can become more noticeable once the other symptoms have reduced or reflect the prevalence of depressed or anxious people as such who receive brain imaging.

3.4. Surveillance and waiting vs. Operational strategy

Patients in the surveillance and waiting group were significantly older than those in the postoperative group (66 against 57 years). There was no statistically significant difference between the Nano score and the ECOG performance status, and age was not a relevant factor for psychological distress. Similar results have been reported above in patients with glioma, where emotional functioning and DT scores were comparable between young and old patients.

The psychosocial burden of an otherwise successful meningioma operation can be durable. Patients can suffer from cognitive, emotional and social disorders, fatigue and sleep disorders for more than 10 years after the operation. In addition, potentially serious accidental results require potentially stressful follow -up, which can also apply to postoperative patients who benefit from monitoring imaging. The same hypothesis could explain the HADS and DT scores higher in this study. Although the fatigue of patients with meningioma has already been associated with anxiety and depression, we have not found such a correlation in our sample of patients.

In our study, there was no correlation between HADS and DT scores and time has elapsed since the operation or diagnosis of the tumor, which indicates that patients may not "accept" their disease even after a significant period of time. In addition, the waiting and monitoring strategy has been associated with depressive symptoms in univariate and multivariate analysis as well as a lower perception of the general state of health, in the SF-36. This is not reflected in observers' scores (ECOG and Nano) - on the contrary, a worse nano score was associated with a lower risk of depressive symptoms. This result could have little clinical value, because the difference was less than 1.0 on a scale ranging from 0 to 23 in patients who did not have focal neurological deficits associated with meningioma.

On the other hand, it is well known that the results reported by clinicians do not always coincide with the results reported by patients. Clinicians often report symptoms; However, the symptom may not be relevant to QVLS or the patient's psychological well-being.

In patients who have undergone a meningioma operation, the socio-economic charge can be explained by the professional situation and the ability to work. However, in our study, there was no association with employment or relational status in the two study groups. Data on patients in psychological distress with WHO II cannot be interpreted due to the small number of cases. There was no significant difference in patients whose tumor had progressed, although this data must be interpreted with caution because the number of cases was low. Therefore, we still do not know how to identify patients who suffer from relevant distress.

According to a multinational survey on patients with meningioma, around a third of those questioned said that the information received from the health care provider at the time of the diagnosis was inadequate and the same proportion of patients received the majority of information on the Internet. This clearly shows that the means to provide information to patients should be improved. A specific questionnaire for meningiomas is urgently necessary to deal with this issue. However, routine screening and psycho-oncological support could be useful to reduce the distress of patients whose intracranial results are even relatively harmless.

3.5. Study limits

This study has several limits. As has been made in a single tertiary neurosurgical center, a major selection bias must be taken into account. Cohorts of patients are not important, which compromises the generalization of data. No neurocognitive test was carried out; Consequently, the association with the QVLS could not be evaluated. Patients were not asked about the current treatment for steroids, which could influence mood fluctuations. In addition, patients with postoperative morbidity were excluded from the study for methodological reasons. This can represent a selection bias. In addition, there was no specific meningiomal questionnaire dealing with relevant questions for these patients. Therefore, some of the relevant problems can remain unidentified.

4. Materials and methods

4.1. Study and patient design

We carried out a monocentric transversal study in the neurosurgery department of a university hospital. The patients were recruited during their external consultations. Two groups of patients participated in the study:

- Those who have been subject to a waiting and surveillance strategy

- And patients who have obtained a good postoperative result after a resection of meningioma. The inclusion criteria were (1) Age ≥ 18 years, (2) the ability to provide informed consent, (3) the agreement to participate, and (4a) the radiological diagnosis of intracranial meningioma for patients under waiting and monitoring strategy or (4b) a histologically confirmed meningioma completely resacued for operated patients.

In order to allow the comparison between patients with asymptomatic meningiomas and patients operated in terms of QVLS, only patients with an excellent postoperative result, that is to say without postoperative meningioma-deficit or associated neurological symptoms (with the exception of light headache (1-2/10 on a digital analogy for pain) postoperative scalp or weakness of the frontal muscles) were included. The exclusion criteria were the diagnosis of another tumor, the indication of the operation due to an important tumor mass, the movement of the midline, hydrocephalus or neurological deficits.

The Ethics Committee of Rhineland-Palatinate, Germany, examined and approved this study (2018-13828). All procedures carried out complied with the ethical standards of the institutional and national research committee and the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its subsequent amendments or comparable ethical standards.

4.2. Surveys

After having signed a consent form, an evaluation of the patient's neurological functions was carried out using the Nano scale and the general state of the ECOG group performance, and demographic and specific data to the tumor. Demographic data included sex, age, level of education (higher in secondary or other), employment, family situation (living with a partner) and comorbidities. Patients were explicitly questioned about psychiatric comorbidities and active or completed treatment. The location, size, growth and histological grade of tumors (for operated patients) were taken into account. The location of the tumor was classified according to convexity, the false, the anterior, medium, posterior pit and the cave saddle/sinus. The time elapsed since the last significant event, that is to say the diagnosis of the tumor for patients under surveillance and the time elapsed since the operation for operated patients, has also been recorded.

4.3. Applied questionnaires

German adaptations of SF-36, DT, HADS and BFI were used for the evaluation of QVLS and psychological distress.

SF-36 is a validated multidimensional questionnaire that measures QVLS; It includes eight scales describing vitality, physical functioning, body pain, general perceptions of health, the functioning of physical roles, the functioning of emotional roles, the functioning of social roles and mental health. The physical physical scores and components can be calculated using the above -mentioned scales.

HADS is a questionnaire measuring symptoms of depression and anxiety, based on 14 questions. The questions interchangeably assess anxiety and depression and provide two scores: the anxiety score (HADS-A) and the depression score (HADS-D). A score less than 8 is considered normal, 8-10 as a limit,> 10 as pathological.

DT is an ultra -clever screening questionnaire that assesses the psychological load (= "distress") on an analog digital scale, from 0 to 10. It is accompanied by a list of 40 problems encompassing emotional, practical, physical and spiritual concerns and is validated for patients with a brain tumor. According to Goebel et al, a score of ≥6 on the DT scale is considered to be a significant load.

BFI is a questionnaire that assesses fatigue based on 10 questions and an average score. The "worst fatigue" of ≥7 corresponds to clinically significant fatigue. The severity of fatigue on the BFI scale from 0 to 6 is considered to be "non -severe" and ≥7, as "severe".

4.4. Statistics

The main result was the difference between the groups concerning the psychological charge as measured by the HADS score. The size of the sample was estimated at 31 patients/group, by considering any difference in HADS values between groups as a zero hypothesis, for a clinically relevant difference of ± 3; If the standard deviation is not greater than 4, the maximum possibility of error of type I = 5% and that of type II = 20%. The categorical data has been described by absolute and relative frequencies, and the continuous data has been described by the average and the standard deviation.

The secondary results were the level of psychological distress as measured by the DT, SF-36 and BFI scores and their association with demographic factors and those linked to tumors. The difference in the absolute values of the scores between the groups was evaluated, after having evaluated the distribution of the variables tested by the Student test or the Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney test. The difference in the distribution of categorical variables has been evaluated by a KHI-DEUX test. The correlation between the scores measuring psychological distress (DT, HADS-A, HADS-D, and the mental component of SF-36) was intended to assess interchangeability and was evaluated using the Spearman RHO. Univariate and multivariate logistics regressions have been used to assess the combination of clinical characteristics with a significant psychological burden. For the regression analysis, the location of the tumor was then classified as false/convexity vs the base of the skull, and the age of the patient was classified as ≥65 years vs younger. Sex, family and professional situation, ECOG performance score and Nano score, tumor size, location, time has elapsed since the last significant event (diagnosis or operation of the tumor), the WHO grade and the progression of the tumor have also been included in univariate analysis. No correction for multiple tests has been carried out. A value P below 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

5. Conclusions

This study demonstrates a high prevalence of psychological distress in patients with meningioma, regardless of the management strategy . A more in-depth evaluation is necessary to identify patients with psycho-oncological support.